Literary Ischia

I am presently moved

by sundrenched Parthenopea,

my thanks are for you, Ischia,

to whom a fair wind has brought me

rejoicing with dear friends

from soiled productive cities.

How well you correct our injured eyes,

how gently you train us to see things

and men in perspective

underneath your uniform light

From 'Ischia' by W. H. Auden, June 1948

[dropcap]While[/dropcap]

in Washington last month at BookExpo America doing what I love best - interviewing smart book people for my podcast - I received an email from a friend who lives in Ischia, Italy, inviting me there to report on Pesce azzuro & Baccal, a first annual tourist festival celebrating the island's ancient food and fishing tradition. I tell him that books are my singular obsession these days, and that they, if anything, will be the subject of whatever writing may come from my visit. He approves, and so I'm here, swept over by fair winds, living the maxim that 'like attracts like'; experiencing gusts of bibliophilic synchronicity as never before.

W.H. Auden, a revered poet whose work I just happen to collect, summered here from 1948 to 1957 and wrote a poem called 'Ischia'. Some of the finest examples of early Greek alphabetic writing, scratched and painted on broken pottery, have been found off the island's coast. Nestor's Cup is on displays at the local Archaeological Museum of Pithecusae. On it is inscribed a three-line epigram alluding to The Iliad. The inscription, in Euboian letters, is the only extant example of a piece of poetry dating from the same time that this epic masterpiece was first spoken.

So, from books to books, Expos to epics, serendipity throws me smack into the cradle of Western Civilization, the start of humankind's written storytelling tradition, the place that inspired some of my favourite poetry.

I've been thinking about living with uncertainty recently, thanks to Canadian writer Madeleine Thien's novel Certainty - free from the frustrating need to know why or how others act, or what the future holds. Knowing we can't control what happens to us or how others behave, it's fruitless to yearn for certainty and yet damned if we don't spend much of our lives trying to nail down the future, order it, set it in stone. Learning to love uncertainty, to revel in negative capability, to accept all that comes, with equanimity and without fear, this is freedom; this, in fact, is what poetry offers: a positive uncertainty.

When I enter my room at the Hotel Villa Durrueli accompanied by friends Gianni and Alessandra I open my suitcase to show off a pair of Shakespeare-themed boxing shorts I'd purchased at the Folger Institute in Washington, and present Alessandra with a slice of Canada: the pancake mix and maple syrup she'd requested. It is then with horror that I notice my laptop gone and my camera and my notepad, all valuable tools necessary to my assignment.

What? The kindly wind that carried me here also blows cold? Deep breaths. Though caught in a whirlwind, instead of being unsettled and angry, I vow to relax. As Gianni puts it: things belong to us until they want to leave; we can buy them, but they decide how long they stay with us. We humans cannot control time. I will savour my stay here in Ischia , without gadgets and the distracting requirement to record. Like Homer, I'll use my memory...and the result will be better.

What brought Auden to Ischia, the biggest island in the Bay of Naples?

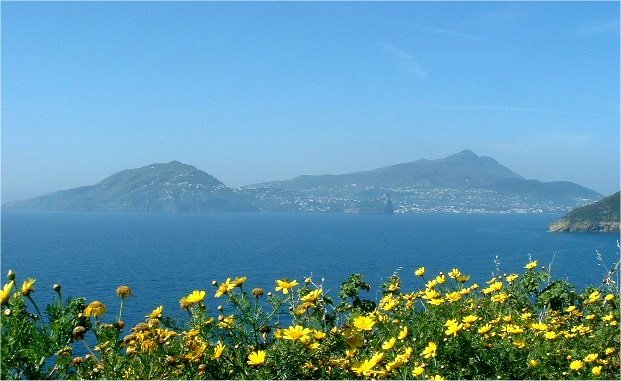

Probably the same things that have attracted saints, pirates, convicts, tyrants, sirens, sunbathers and invalids for centuries: volcanically-driven thermal water, beaches, food, flora, mythology, sunlight and the pure poetry of this green island's land and seascapes. Called 'Pitecusae' in ancient times, Ischia was colonized in turn by the Greeks, Romans, Saracens, Turks, and Aragonese. Proof of this can found in the ruins, the outposts, towers, and "tufa," or rock shelters, that stand scattered around the island. This visible history, these reminders of a storied past must, I think, have appealed to Auden. Living here, where Homer sailed and Odysseus searched, no doubt inspired poetic expression. Auden's Shield of Achilles won the National Book Award in 1956.

From April to October Ischians typically wake to long, bright sunny days, and wind-down to dreamy, sunsetted evenings. Hot, dry summers, mild winters, and rich volcanic soil combine to encourage tropical and sub-tropical Mediterranean plant-life all over the island. The Southern side, with continuous exposure to direct sunlight, favours palms, cacti and agave plants; the North, in shade cast by Mount Epomeo, bares chestnut trees, holm oak, cypress, cork, cultivated almond, and olive trees.

Today's Ischian mud originates from yesterday's hydro-volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. It's found in deep, narrow gorges that slope down toward the sea from Epomeo and surrounding hillsides. Hot and rich in mineral content, Ischian spring waters and earth are deemed officially suitable for the therapeutic treatment of rheumatic, arthritic, respiratory, dermatologic, gynecologic, gastrointestinal and other less savory disfunctions. These boiling springs, as Auden put it 'betray her secret fever, Make limber the gout-stiffened joint and improve the venereal act.'

Baths and thermal gardens built centuries ago around these springs dot the island. Some gush hot water into the sea, others blow steam through cracks in the earth. These 'Fumaroles' can be seen on the sides of Epomeo, particularly on cold days, and can be felt in small caves, called stoves or sudatori (from the Italian meaning to perspire). An old legend says that the Giant Tifeo was chased from Olympus by Jupiter and then chained and dropped into the Tyrrheanian Sea. His restless body is said to have formed Ischia and so you'll find places here named Testaccio (Head), Ciglio (Eyelash) and Piedimonte (Foot). Tifeo struggled in the sea, and although beaten, island lore says that he breathes still. The Fumaroles prove it.

An island with lots of beaches, Ischia, thanks to all its rich lava, also boasts beautiful countryside where houses carved from ‘green’ volcanic stone are set against verdant tropical and sub-tropical folliage. 'What design', to quote Auden again, 'could have washed with such delicate yellows and pinks and greens the fishing ports that lean against ample Epomeo, holding on to the rigid folds of her skirts'?

The local cuisine is also very colourful. Rabbit has for centuries been cooked in terracotta baking-pans with garlic, wine, little tomatoes, lard and local spices. The famous Paranza dish sees all sorts of tasty little fish rolled together in flour, and pan fried in lots of oil. It’s hard to estimate how many thousands of these little minnows I ate during my stay, but each and every one tasted delicious. Ischia is known too for its honey which has a unique consistency and taste; its bread, and its variety of vegetables, in particular its tomatoes, and two unusual beans, the purple-red colored piper and the black nuanced fascist.

On the first full day of my visit we lunch at one of the most perfectly kempt bed and breakfasts I've ever seen. As with much on this island, everything – man and nature made - has its place, and that place owns a singular decorous merit. The kitchen walls, the cooking utensils, food on the plate, the placement settings, garden tools, the vegetables, the window sills, the ocean…all exude artistic sensibility. We inhabit a picture where life and its living are tempered with tender brush strokes. Set high up in the hills, Pera di Basso is surrounded by a beautiful wet/dry, azure/emerald view. I’m particularly taken with the broom, Ginestra, as the plant is here called, which scatters the mountain sides. Leopardi wrote a poem by this name. And so too did I:

Ginestra: A Tribute to Ischia and Auden

Soft canary fleur de lis

under Italian sunshined mountains

Were your lemoned swords alive

when Achilles’s anger raged.

Saw you Homer and the poets?

As I rejoice with friends

Tell me the story I live, and stay alive

To translate my heart's language.

Pierce this Goddess's perfect watered image

And heal a happy stranger's eyes

Ischia is divided into six communities, among them Ischia Porto with its splendid Aragonese castle, and Forio, on the west coast, where Auden and others including Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote, hung and drank. While there I visited his favourite watering hole, Maria's café, sat at his favourite table, and listened to an old man tell of how one night the great poet, disgusted at the place being closed, pissed right on its doorstep.

Villa La Colombaia the spectacular home of Italian movie director Luchino Visconti is close by. Although now a bit run down, the property still gives off a rich sense of what it must have been like when the powerful and famous luxuriated in it during the forties and fifties. Pierpaolo Pasolini, Sir William Walton, Eduardo De Filippo, Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, Alberto Moravia, Renato Guttuso, Auden, Pablo Neruda, Jackie Kennedy, Aristotle Onassis...all were guests at one time or another. Throughout the house are dramatic black and white stills from scenes in many great Visconti films, including a moving one of a melancholy Dirk Bogarde in 'Death in Venice'. Born into a noble, wealthy family (one of the richest in northern Italy) Visconti lived for many years at the centre of Italy's cultural life. He and his father were both openly bisexual. William Walton, one of the most important British composers of the 20th Century, lived in the villa next door with his Argentinian wife Susana. Together they planted what is today a spectacularly beautiful garden. La Mortella contains a thriving, kaleidoscopic range of flowers and tropical and subtropical plants from all over the world.

Why then would Auden ever want to leave this paradise? In 1956 his houseboy Giocondo attempted to cash a salary cheque for 600,000 lire. Whether the extra zero was forged, or mistakenly added by Auden, the bank refused to cash it because there wasn't balance enough to do so. Giocondo insisted the extra money was for services rendered and went around telling anyone who would listen that Auden, fearful of his partner Chester Kallman's jealousy, had reneged on his gift. This poisoned air, coupled with the fact that his landlord, upon hearing that Auden had just won the $33,000 Fettrinielli Prize, had jerked up the asking price of the place well beyond what it was worth (Auden had wanted to buy it) - the loss of his father, and an influx of limey lushes, all combined to precipitate an exit. In ‘Goodbye to Mezzogiorno’, written in 1958, Auden says:

To go southern, we spoil in no time, we grow

Flabby, dingily lecherous, and

Forget to pay bills

Go I must, but I go grateful (even to a certain Monte) and invoking

My sacred meridian names, Vico, Verga, Pirandello, Bernini, Bellini,

To bless this region, its vendages, and those

Who call it home: though one cannot always

Remember why one has been happy,

There is no forgetting that one was.

His next stop was Kirchstetten, Austria, because it provided "a Mediterranean life in a northern climate with a drinkable wine and an opera house of high standard." He died in Vienna in 1973 at the age of sixty-six. Summers spent on Ischia were among the happiest of Auden's life. Speaking once of the joys of going abroad, he said 'the great relief is escaping from a non-humanized, non-mythologized nature and getting back to a landscape where every acre is hallowed.' This is as apt an explanation of why he loved Ischia as one could hope for - one that provides reason enough for all of us to do the same.

Plan your trip to Ischia here.

Copyright © Nigel Beale